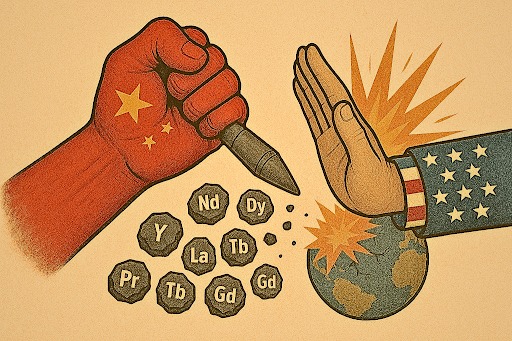

What happens when the world’s factories depend on a handful of minerals, and one country holds the keys to their supply? As trade wars intensify, rare earths have become more than just raw materials – they are turning into powerful weapons in the global economic battlefield.

Following tariff attacks from the US, China abruptly paused its production and shipment of refined rare earths, provoking severe supply chain disruptions. Because these minerals are critical to make strong magnets used in everything from vacuum cleaners to cars, their shortages rendered car factories non-operable.

Ford halted a factory line in Chicago, while automakers in China and India had to curtail their production

At first glance, everything worked out perfectly for China. It achieved what it wanted, and recently, President Trump has announced that the US would extend/protract their tariff/trade truce with China. The fact that an aggressive, decisive person like Trump had to pause his policy to alleviate US-China trade tensions clearly demonstrated China’s overwhelming power.

In fact, China’s chokehold in the rare earths industry is what causes investors and producers to panic. It can force the shut-down of major factories at the stroke of a pen. China wants to take advantage of its heft/use its heft to threaten other countries. This happens amidst global talks of “de-coupling” from China, which clearly goes against the country’s goal of indigenizing the supply chains to achieve self-sufficiency. The weaponization of rare earths might be effective in the short term, but it may backfire in the future.

We must acknowledge, firstly, that China’s dominance does not stem from any exclusive control of the minerals or technological prowess involved in the mining process. It, instead, comes from the country’s ultra-efficient and large-scale refining process unmatched by other countries’. It is able to mine and process minerals on a large scale due to its willingness to accept environmental consequences, which would not be approved in Western nations due to their rigorous environmental standards. The country’s advantage/edge, furthermore, is cemented by its 1.4 billion population, which provides an abundant and cheap source of labor.

Chinese efforts to weaponize this industry might spur attempts to find alternative suppliers. After the spat in 2010, Japan invested in rare-earths mines and began building stockpiles to better absorb geopolitical shocks; as a result, the country’s dependence on China’s minerals has descended from 90% to 60%. Similar projects are happening in the US, with mining corporations receiving generous subsidies from the government to literally “reinvigorate” the mining industry.

Another thing about shortages and crises is that Xi Jinping fails to grasp their unappreciated role in spurring innovation. European carmakers have engineered work-arounds so that their cars’ motors do not rely on rare earths. Some start-ups have proposed methods that help recycle these minerals. Just like how America’s sanctions of chips encouraged Chinese firms to design and fabricate their own processors, China’s export controls might provoke a similar reaction. Even a small erosion of China’s share in rare earths could weaken its power disproportionately, allowing customers more room for maneuver.

– Bui Hai Dang